The first big wave of Chinese immigrants came to America in the mid 1800s escaping poverty in China. They arrived on the West Coast during California’s Gold Rush. Anti-Chinese sentiment came in full force because the newly arrived Chinese were perceived as creating job competition for miners and other laborers. The hard-working Chinese were willing to work for lower wages than most others workers were.

In 1877 in San Francisco, railroad workers began to strike over wage cuts and poor working conditions. A meeting to express sympathy for the strikers resulted in attacks on the Chinese, and quickly a mob turned on the Chinese neighborhood of Chinatown. Around the same time Irish immigrant Denis Kearney organized the Workingmen’s Party of California and called for the end of Chinese immigration, nicknamed the “yellow peril.” His party fell apart in a few short years, but by then the “yellow peril” had become a national issue. Anti-Chinese attacks and riots continued throughout the 1870s and 1880s.

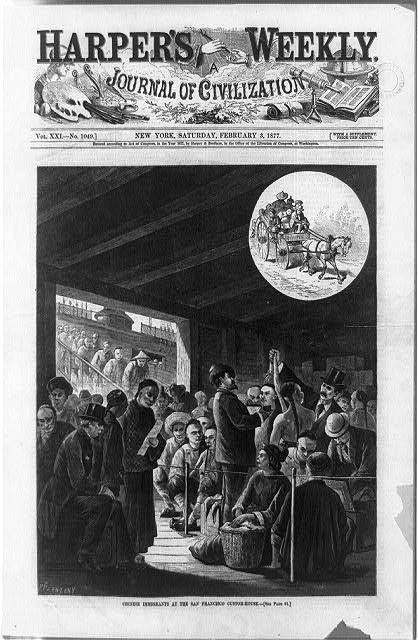

A Harper’s Weekly magazine cover from 1877 shows throngs of Chinese immigrants entering San Francisco. Image courtesy of the Library Of Congress.

In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, prohibiting Chinese immigration and naturalization. The Chinese were the first group to be barred from entry to the U.S. based on ethnicity, or nationality. For 10 years, no Chinese laborer was admitted to the U.S. Those already here were ineligible for citizenship. In 1892, Congress updated the law with the Geary Act which extended the ban for another 10 years. At its expiration, Chinese immigration was made illegal indefinitely.

Discrimination in housing and jobs led to concentrations—and segregation– of Chinese in “Chinatowns”. Some states restricted Chinese from owning property. Few industries were open to the Chinese for employment outside of restaurants and running laundries.

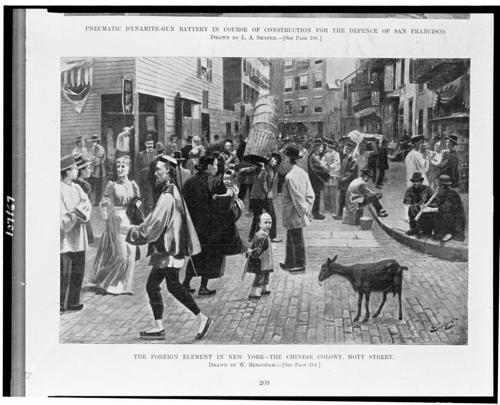

An 1896 depiction of Chinatown in New York City, published in Harper’s Weekly. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

In 1910 Angel Island, an immigration station six miles offshore of San Francisco, opened to mostly Asian immigrants. Chinese who could claim a Chinese-American parent were allowed to enter, as well as officials, teachers, merchants, and students. However, 30% of the Chinese who attempted entry were denied. Those who appealed this were held in prison-like barracks for months.

In 1943, Congress purged all exclusion acts because China was an ally against Japan in World War II. However, limitations still existed. Only 105 Chinese were allowed entry per year, but Chinese-Americans were able to become naturalized citizens. The Immigration Act of 1965 loosened the restrictions further allowing 170,000 immigrants annually from outside of the Western Hemisphere, with a limit of 20,000 from any one country.

In Rockford, Illinois the first permanent Chinese settler was William T. Moy. In the early 1900s he opened a hand laundry at 108 South 3rd Street. In 1915 Hop Wah opened a laundry on Seventh Street that would stay open until 1930. Hop Wah was born in California to Chinese parents. The number of Asians in Rockford remained small – under 100 – until after World War I.

Seek Loy Wong, Charley Don’s son, sits at the center of the photo in the striped shirt. He is surrounded by his family as they take a picture in the back of the laundry. Image courtesy of Patricia Fong.

Among the arrivals after World War II was Charley Don, who emigrated from China and spent a few years living in Chicago. When he moved to Rockford in the early 1950s he opened a laundry on Court Street across from Court Street Methodist Church. In 1956 he moved the laundry to Mulberry Street and remained in business until the 1970s. Although Charley Don’s son and grandchildren lived in Rockford as well, at least one member of the family was precluded from coming to the United States until after the passage of the Immigration Act of 1965.

Steve and Lanny, Charley Don’s grandsons, are pictured here in front of the Court Street laundry around 1956.